Some things have been bothering me for a while now, about programming as an activity and the software engineering discipline from which it follows. As usual, I’ve been struggling for a while to articulate the insights that I’m grappling at. But let me finally commit to trying, at least.

I’ve been spending a lot of time with infrastructure in my current role, wrangling automation, troubleshooting environments, configuring and optimising builds. Operating machinary that pushes buttons and pulls levers on other machines ad infinitum. In this world the conventional notions of software design and architecture seem to be hidden away in a galaxy of configuration details, sharded amongst the plethora of YAML files, and smothered under the avalanche of container images, build scripts and orchestration tools.

We often justify all this work as necessary and driven by the inherent nature of the world large-scale, distributed systems we’re working in. Unfortunately, this distributed systems world is still a very messy space where technology, culture and methodology coalesces into some supermassive complex, adaptive web of socio-technical interactions. I tend to think of it as a giant multi-dimensional Jenga game.

I try to cope with this by doubling down on first principles. Easy-isn’t-simple. Keep things SOLID. Draw boxes and lines in my mind to model aggregates, properties and relations of the Rube Goldberg machine that produced these... log lines. It’s difficult to look at all this activity and not feel a little overwhelmed, a bit perplexed and suspicious about where we are and where we’re going as an industry and discipline. And then I see the tools we have been offered up to help us, and then... despair:

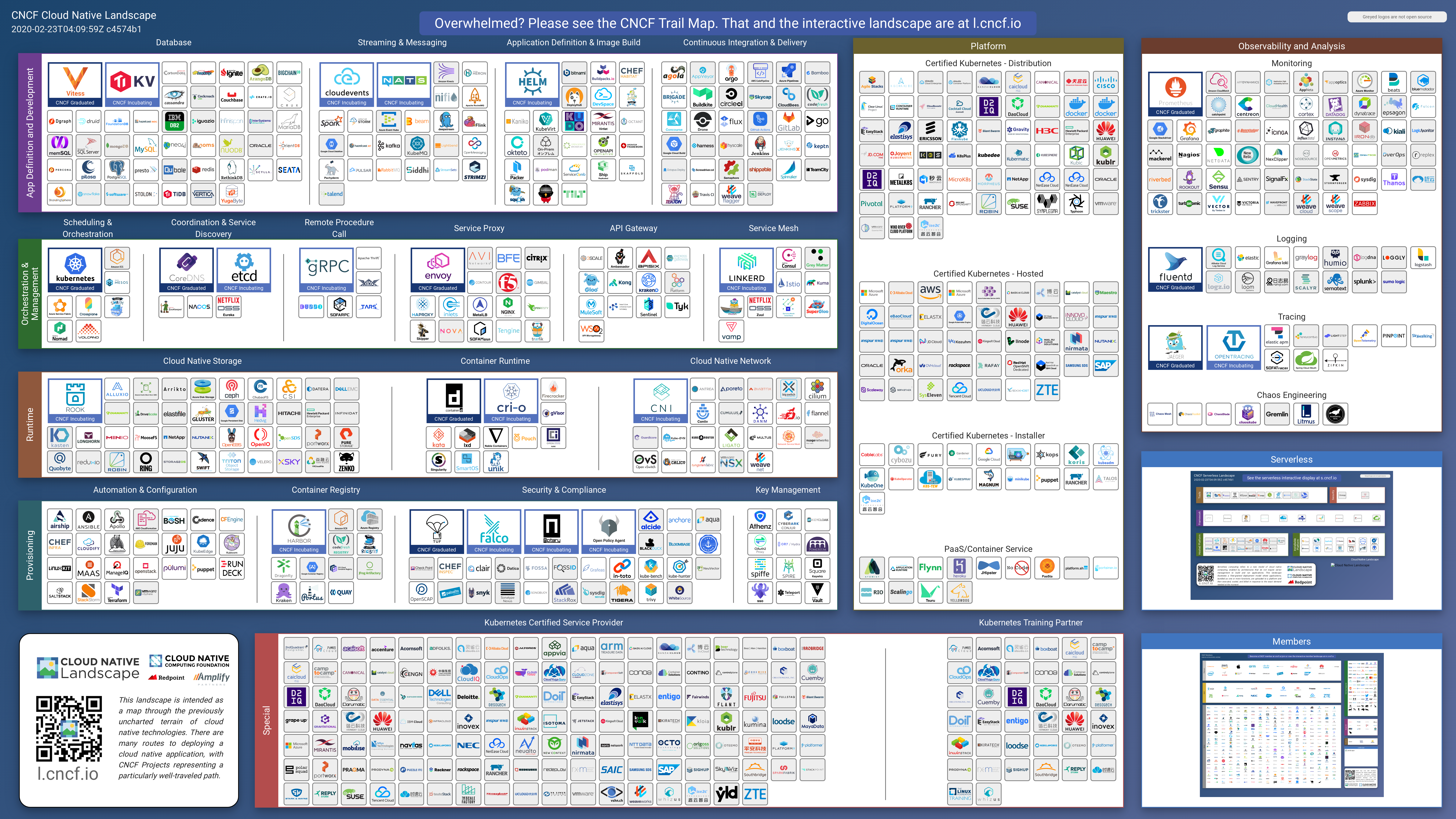

The image above illustrates the ecosystem of tools used to build and maintain a modern software system today.

The image above illustrates the ecosystem of tools used to build and maintain a modern software system today.

It’s difficult to reconcile the picture above with the notion of writing software as a problem solving activity, realised by humble text-editor and compiler/interpreter. But perhaps this vision was always only a myth, cooked up by well-meaning, rational people in ivory towers.

Still, it raises the question: how did we get here? This feeling is quite possibly exemplified in the following statement by Jonathan Edwards, a respectable figure in the language design community.

Programming today is exactly what you’d expect to get by paying an isolated subculture of nerdy young men to entertain themselves for fifty years. You get a cross between Dungeons & Dragons and Rubik’s Cube, elaborated a thousand-fold. https://t.co/Mug9k7ioIG

— Jonathan Edwards (@jonathoda) July 31, 2018

As a nerdy guy who does indeed enjoy Dungeons and Dragons and Rubik’s Cube, this struck a chord. But it’s not an empty, inflammatory statement, as Mr Edwards expounds further:

I’m serious: Dungeons & Dragons requires mastery of an encyclopedia of minutiae; Rubik’s Cube is a puzzle requiring abstract mathematical thinking.

While I don’t agree with the entire article, it’s a compelling description of sofware development in practice. Programming, being the most elementary activity in software development, does seem to superficially favour those who have the requisite level of monomania to master these minutaie. But far more insidious than that, is that it hints at a design philosophy and solution approach that is incrementalist and potentially suffering from Einstellung.

I suppose this isn’t a novel insight or complaint. Maybe it’s just a rite of passage that all developers must go through: a mid-career crisis that forms a better appreciation for software complexity, after getting burnt for the umpteenth time, finally learning... Fortunately, I know there are many movements, practices and tools before that offer an escape to lift us out of “The Tar Pit” and into the realm of deliberate design and problem solving. Things such as Domain Driven Design, Functional Reactive Programming, even the venerable Design Patterns offer some escape routes. But putting them to practice often feels like trying to steer an oil tanker, against its own tremendous momentum.

I’m hopeful that these approaches will win. But not in the same way that Agile has “won”. Software problems cannot be solved by simply playing with stickies and JIRA reports. These are artifacts and tools of bureaucracy, of managing work from a production-based worldview1, and ill-suited for problems of software engineering which is knowledge work. I’ve come to believe (cautiously) that the problems of software engineering are fundamentally about dealing with complexity in its many forms. This requires tools and approaches rooted in design, critical thinking and problem solving - general skills that people can excel at when given the chance to be people in their own full complexity instead of being hostage to methodology and process.

Generally, I think we’re reaching new levels of scale and complexity at which incremental approaches to design are insufficient. This will force the fore-runners in the field to return to the fundamentals and experiment. Perhaps the advent of serverless and deployless represents the start of this shift2. Hopefully we can learn and apply that same philosophy in our own daily work. Hopefully, reaching for fundamentals can give us more leverage and help us sweat the right details. More on this later.